Technical Implementation

Camera and sensing: choosing stability over convenience

A key early decision was how the system should see the workspace.

Alternatives considered: We considered using Kinova's onboard camera for a cleaner setup. However, the camera's reference frame moves with the end effector, and the arm's positional error can reach ~1 cm—exactly the same scale as the placement tolerance target. It also forces a "home pose" overhead for full-table visibility, slowing the human workflow.

Final choice: a fixed webcam mounted ~1 m above the table to capture the full workspace continuously, outside the arm's operating volume (stable reference frame, no extra robot motion overhead).

Robust gesture recognition with normalized landmarks

Gesture recognition is powered by hand landmarks (21 keypoints per hand) and simple geometric tests—built for reliability rather than novelty.

What made it robust: Instead of using absolute distances between fingertips (which breaks across different hand sizes and distances to camera), I normalized measurements by palm scale. This made the gesture classifier invariant to hand size and depth, improving consistency across users.

Design intent: keep it fast and interpretable—so failures are diagnosable and latency stays below the interaction threshold (targeted under ~200 ms).

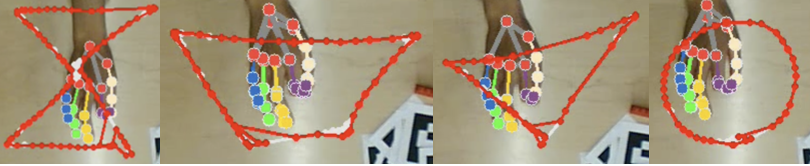

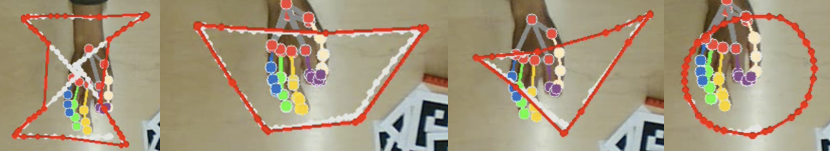

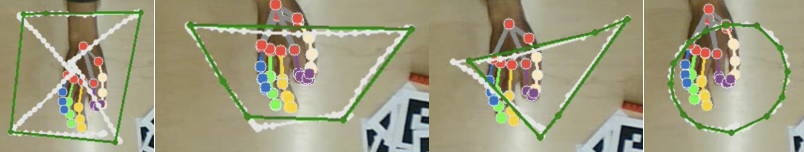

From noisy finger paths to fence-ready geometry

The hardest “thinking” part of the system is turning a noisy trace into a clean outline that preserves corners and is constructible with physical fence segments.

Hard constraint: every edge between consecutive vertices must exceed the 5 cm fence length, otherwise the robot would be asked to place segments that physically can’t fit.

Design exploration: I tested each algorithm family across many traces (convex, concave, and “messy” user shapes) and judged them on: vertex fidelity (especially concave corners), constructibility (edge length), and stability.

1. tight α-concave hull (α=0.1): bad vertex interpretation + too many short edges (not fence-constructible).

2. loose α-concave hull (α=0.5): better on convex corners but still collapses concave features; still produces short edges without extra processing.

3. Convex hull + distance smoothing: constructible edges, but convex hull fundamentally cannot represent concavity; also missed important convex vertices in some traces.

4. Ramer–Douglas–Peucker (RDP) + distance smoothing (final): handled both concave and convex shapes, preserved key vertices, and could be recursively tuned until edges satisfied the 5 cm constraint.

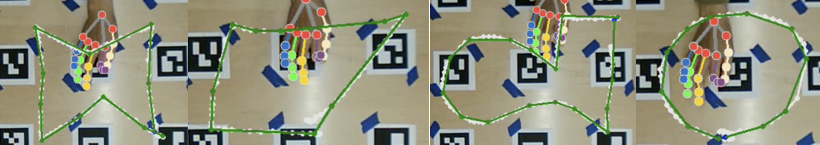

Aligning vision space to robot space

The full system only works if the CV output becomes a valid robot input.

I integrated the modules by converting the camera-derived trace coordinates into the robot’s reference frame using transformation matrices and scaling, so the planned fence poses match the Kinova control interface.

Research Outcomes

Insights on Human-Robot Collaboration

The research revealed key insights into how humans and robots can effectively collaborate on creative tasks. Participants found the gesture-based interface intuitive and appreciated the robot's ability to maintain precision while they focused on conceptual design.

The study demonstrated that combining human creativity with robotic precision creates opportunities for new forms of collaborative design work, with implications for manufacturing, education, and creative industries.

Impact & Future Work

Extending from “execute my sketch” to real co-creation

This research contributes to the growing field of human-robot collaboration by demonstrating practical methods for co-design. The findings have implications for future interactive systems where humans and robots work together as creative partners.

Next steps include:

User Studies with designers/planners to refine gestures, feedback, and failure recovery.

Object Recognition on the table so the robot can reason about existing elements, not just place along a new outline.

Design suggestion features to compute-and-suggest alternatives (spacing, accessibility, circulation) while keeping the human in control.

"This work explores an exciting new paradigm where robots become active collaborators in the creative process, not just tools."

hrc² Lab, Cornell University